The ongoing debate about the representation of temperatures on weather maps is reaching new heights in Spain, as AEMET (State Meteorological Agency) adjusts its color scales to the reality of the warmer climate. While critics decry an alleged exaggeration of global warming through “warmer hues” on social media, experts clarify the creation and adaptation of these maps.

With the onset of summer and its associated heatwaves, the discussion surrounding the coloring of temperature maps flares up repeatedly. The focus here is particularly on accusations that AEMET and other meteorological services are exaggerating the extent of global warming by using warmer color scales. VerificaRTVE, together with AEMET, the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF), and RTVE’s meteorological team, has addressed this narrative to shed light on the matter.

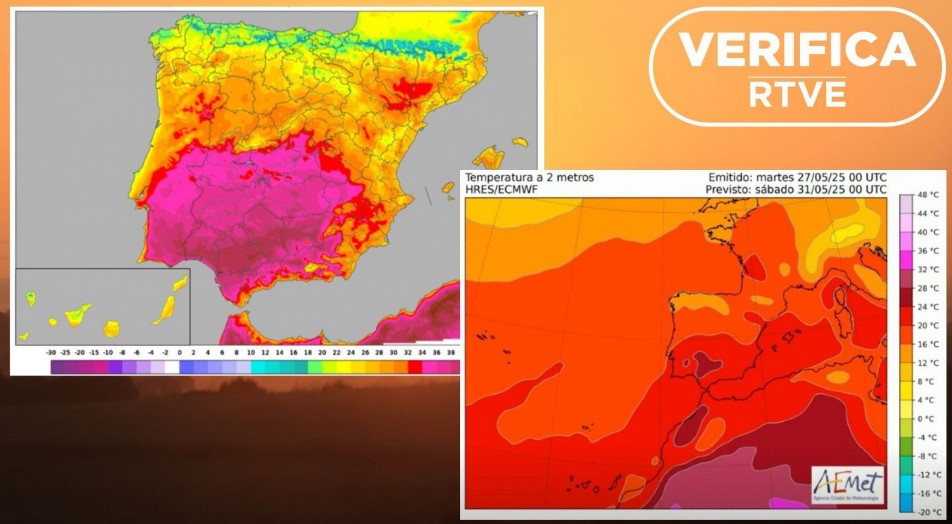

The end of May 2025 saw Spain’s first major heatwave of the year, with temperatures reaching around 40 degrees in many areas. AEMET warned on platforms like X (formerly Twitter) on May 27 of an “extraordinary episode of maximum temperatures, typical of mid-summer, especially in the valleys of large rivers.” An accompanying animation of the temperature forecast from May 27 to June 6 sparked a wave of criticism on social media.

Users complained that the color scale suggested alarmingly high temperatures, even for values perceived as “mild” or “normal.” Posts like “@AEMET_Esp publishes images where the mild and normal temperature […] aims to adapt the apocalyptic narrative and color the map with the colors of Mordor” or “The comfort temperature is 24 degrees, but for whatever reason, AEMET shows it in orange” illustrate the sentiment. Such publications, which showed different maps with varying color scales, significantly contributed to the confusion.

It is important to understand that while the data published by AEMET on May 27 was shared by them, it was originally provided by the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF). This intergovernmental organization, comprising 21 European states (including Spain) and 13 associated countries, provides raw data from which AEMET and other services create their visualizations. Rubén del Campo, spokesperson for AEMET, confirmed to VerificaRTVE that these ECMWF data are used to create “animations like those in the tweet and other similar ones for ad-hoc use on social networks.” The criticized maps showed temperatures at 2 meters above the surface with a scale from -20 °C to 48 °C. The controversy arose because the scale displayed yellow, orange, red, and violet tones for temperatures above zero. Del Campo emphasizes that this scale, agreed upon by more than thirty countries, is published by the ECMWF on its website and covers a temperature range of 68 degrees, grouped into 17 color tones. Therefore, it is “unavoidable to use cold and warm colors in some parts of the scale.”

The ECMWF assures that AEMET has access to its data and creates its own color charts from it. They also state that they have not changed their temperature maps in recent years: “We make these colors as meaningful as possible (e.g., blue for cold and red for warm), but there are no internationally agreed standards.” For the ECMWF, it is crucial “to allow users to quickly and easily read the values,” and they try to make the scales valid for everyone.

On AEMET’s official website, two different numerical models are published: Harmonie-Arome, which shows data for the Iberian Peninsula, the Balearic Islands, and the Canary Islands, and the CEPPM, which displays temperatures for the entire North Atlantic. “For sub-zero temperatures, white and violet tones are used, and warmer tones appear from 32 °C. The range is 80 °C, and there are 22 different intervals, so again, it’s unavoidable to use cool and warm tones on the scale,” explains the AEMET spokesperson. This modeling corresponds to AEMET’s publication of June 6.

AEMET assures that its color scale has not changed since the agency was founded in 2008. Nevertheless, AEMET shares both its own maps and those created by CEPPM on social media. Rubén del Campo admits that, regardless of the model used, there are always discussions about the color scale when high temperatures occur: “Whenever there are episodes of high temperatures, there is excitement about the scale used in the maps. This happens not only with the maps of the State Meteorological Agency but also with those of television weather forecasts and other meteorological services.”

However, Del Campo emphasizes: “At AEMET, we believe that the expected temperature is truly important, especially when it is an extraordinary episode like the end of May.” To increase coherence between the different communication channels, AEMET is working on adapting the CEPPM scale maps to the scale they use on their own website. He confirms that a warmer climate like Spain’s is better suited for the scale used by AEMET than for that of the European Centre.

RTVE, Spain’s public broadcaster, also uses its own color scales in its news broadcasts. Here, colors vary every two degrees: Up to 20 degrees, various blue or green areas are used, while higher temperatures are represented by warm colors from yellow to black. Albert Barniol, presenter of the TVE program “El Tiempo,” explains that the program always uses the same color scale and has only made minor adjustments. “Initially, we placed red for 30 °C and black for 40 °C, but we had to adjust it to 48 °C because higher temperatures were recorded.”

In addition to accuracy, meteorologists value the comprehensibility of the maps. Small nuances can be made at the meteorologist’s discretion, but the most important thing is “the absolute value,” which always remains the same and sets the legend accompanying the graphics. Barniol also highlights differences between the CEPPM-based maps shared by AEMET and those of AEMET and TVE: The CEPPM models are “numerical prediction models” for medium-term forecasts with lower spatial precision and a resolution of 4 degrees, while AEMET and TVE maps offer a more precise resolution of 2 degrees.

Weather forecasting has a long history: The first weather bulletin was published in 1893, the first radio broadcast took place in 1926, and in 1956, weather information reached television. Despite this long tradition, meteorology, especially in the context of climate change, remains a target of misinformation on social media. VerificaRTVE offers a test on World Meteorological Day to sensitize the public to misinformation about the weather.